text copyright © Don Davis

On Space Art

The categories of fantastic

yet believable imagery explored by devoted artists keeping track

of recent developments and discoveries included distant locations,

distant times, and finally distant places in the Universe.

Alma-Tadema comes to mind as an artist who used

ongoing archeological discoveries in his portrayals of ancient

scenes. By choice or by neglect, the late 19th century period

the works were done in can be determined by the hair styles shown!

At the start of the 1900's Charles R. Knight became the old master

of prehistoric life, painting dinosaurs and mammals of past eras

using his considerable knowledge of animal anatomy to help fill

in what the fossils left us to guess at. His mammal work has fared

better than his dinosaur work, but our opening visions of the

subject at that time are thus preserved.

The desire to see into exotic realities

we can never directly experience can be satisfied by an artist

using whatever is known of the subject as a starting point, and

trying to fill in the unknown by educated guess, instinct, and

imagination. The emergence of Astronomical art as a means of showing

what such and such a distant place revealed by our enlarged inquiries

might look like is the latest of several such schools of painting

which have attracted great artists in recent history.

The dawn of space art roughly coincides

with the opening decades of the 20th Century, largely with the

emergence of paintings of space scenes in the Illustrated London

news by Lucien Rudaux during the 1920's. A generation later Chesley

Bonestell would practically recreate the genre singlehandedly.

British artist Ralph Andrew Smith also created detailed portrayals

of a post war Lunar Landing proposal by the British Interplanetary

Society.

As our knowledge of the Universe

has grown the painters inspired by our new insights and the range

of their visions have themselves multiplied, as have the methods

available to them.

The website of the IAAA, the International

Association of Astronomical Artists, has information

on this movement and works to continue the tradition. Here is

some info on the greatest luminary of this tradition.

On Chesley Bonestell

Chesley Bonestell was

a contemporary of Maxfield Parrish, and indeed some of their painting

techniques were similar with one fundamental difference. Parrish

painted like a human lithography press, laying down first the

yellow 'layer' applied in it's prearranged strength to combine

with the red and blue layers applied also in amounts carefully

calculated to glaze together and form the desired colors after

being layered atop each other!

The May 29, 1944 LIFE magazine contains an article

on the Solar System which probably introduced Bonestell's space

art to more people at one time than any one place, the series

of Saturn seen from various moons. In this group is the first

version of the famous 'Saturn seen fromTitan' piece, the vast

Saturn filling the sky of Mimas with the tiny figures 'added for

scale', and the Iapetus scene whose mountains made a comeback

for the Antares scene mentioned later.

The March 4 1946 LIFE contained a 'trip to the Moon'

article where more Bonestell art, which was to appear in 'Conquest

of Space', (his classic) first appeared. 'The World We Live In'

was a large 'coffee table book' based on an extended nature series

published in Life. The resulting book was probably the greatest

gathering of artistic talent ever applied in one volume to the

sharing of the wonders of nature with the public.

The paintings of Chesley Bonestell would, more

than any other artist, gave life to space art, creating as never

before the sense of other worlds being places of their own rather

than dimensionless dots on a sky chart. His magnificent painting

ability was honed by a deep understanding of perspective and lighting

effects gathered while pursuing careers of first architectural

rendering, then matte painting for Hollywood. His matte work graces

the backgrounds of many a fine film in the 1930's and 1940's,

including 'Citizen Kane', widely regarded as the greatest film

ever made. Another 'Class Act' he had a hand in was the design

of the corner gargoyles of New York's Chrysler Building, one of

the classics of American architecture. During the planning of

the Golden gate bridge he painted studies of how the finished

structure would appear. He was in effect a human CAD system for

that task!

After World War Two the V-2 and

the Atomic bomb made speculation of space travel seem less of

a pipe dream, and a symposium on space flight brought to the public

a maturing vision of the possibilities at hand. From this series,

hosted by prominent author Cornelius Ryan, emerged a series of

1950's articles in Collier's magazine and three widely seen Disney

programs. In a series of books with Willy Ley and Werner Von Braun,

Bonestell painted the scenery on the Moon and Planets as it was

believed to be, embellished with dramatic license within the bounds

of what was known at the time. The paintings were endowed with

realistic treatment of lighting and shadows and other painterly

means to make the picture look plausable. The hardware being imagined

at the time to bring people to these exotic places was painted

with the crisp realism of a bridge or skyscraper design.

In 'The World We Live

In', the beginning and end of the book featured Bonestell's visions

of the beginning of the World and the infinite cosmos beyond it.

When my Mother and Stepfather moved to Menlo Park, we had as next

door neighbors an eccentric artist couple, Mary Anne and Ted Ligda.

They were especially good to my brother and I, anxious to allow

potential artists to dabble in painting. They had a fully furnished

upstairs artists studio with immense supplies of oil paints and

brushes.

I first seriously tried to learn oils in that small

wooden room with many little shelves built in to the walls apparently

tailored to the size of science fiction pulp magazines. There

were row after row of issues of yhe science fiction magazines

Fantasy and Science Fiction, Astounding, Analog, and Galaxy, mostly

from the 50's. I soon noticed the variety and ability of the artists

who painted the covers. Fantasy and Science Fiction in particular

would occasionally do a wraparound cover for an exceptional painting.

Artists like Emshwiller, (he only used the first four letters

in his signatures), Mel Hunter, Kelly Freas, Schonherr, Van Dongen,

and of course Bonestell could be seen often on newsstands in the

golden age of Science Fiction in the 1950's. F&SF in particular

seemed to showcase Chesley's work, with works from those prepared

for the books Conquest of Space, Exploration of Mars and other

space books often appearing. Seeing such a large number of new

Bonestell paintings at once was a revelation for me, I admired

the realism and wondered how he accomplished it. When I pointed

out Bonestell's work the Ligdas instantly knew who Chesley was,

and even knew that he lived in nearby Berkeley!

Soon I had looked up Bonestell's telephone number

and called him up. God knows what he made of me, but the fact

that I asked good questions made the difference. Among other things

I asked about artists I admired, and learned that Charles R. Knight

had been dead for 20 years, and that he didn't think much of Mel

Hunters work. One of the Galaxy issues had an article on the making

of the film 'Conquest Of Space', and when I asked him what he

thought of the film he unhesitatingly said in a barely restrained

manner "I hated it!" Called in as matte painter and

technical advisor, he had in numerous paintings taken our vague

vision of Mars and filled in the details using his scenery painting

skills. Based on the best knowledge of the day, there would only

at most be eroded remnants of mountains, and flat rolling light

orange sands. The jury was still out on the nature of the dark

regions and the seasonal 'wave of darkening' which in earlier

decades was cited as possible evidence of seasonal changes in

widespread vegetation.

Bonestell visited the Mars landing set for the movie

and saw a wide container of dark beet red sand with chunks of

obsidian sticking out of it. He at once protested that this wasn't

the way it was, and naturally he was ignored. When the final film

came out it was such an empty mockery of the book that Chesley

became very cynical of the movie business. He in fact warned

me to stay out of Hollywood! Now when I see 'Conquest of space'

it is a sad irony that the only thing that separates that awful

film from the 'Golden Turkey Award' status is the fact that Chesley's

matte paintings look so good.

I'm sure I bugged him just a bit

too much, but I convinced him to have a look at my art, and he

told me of an upcoming party he was going to at his agent Bill

Estler's house. Estler was a man active in arts circles

of the Midpennensula. In January '69 it was arranged that I bring

a few paintings to nervously present to the Master, My ship in

a dried out ocean bottom painting, a Moon painting, and a few

others. As I arrived I saw Estler was an avid art collector and

owner of a treasure laden house on Lincoln street in Palo Alto.

Once you went into the long hedge lined driveway, you found yourself

passing through a gate into a tree sheltered sanctuary, with a

generous back yard filled with paths, fountains, and plants woven

into mature patterns on trellises and small statues. His house

was a residential museum.

I asked Bill what his oldest possession was, and he

showed me a simple bronze vase from Imperial Rome.

In an outdoor dinner party in his back yard he introduced

me to Chesley. At 78 he looked old but far from infirm, with an

air of sternness laced with humor. Chesley was truthful but kind

to me as I showed him my paintings, seeing enough to encourage

me to study perspective and invited me to show him more work later.

This was the start of an extended series of visits with Chesley

and his wife Hulda, during which many a story and word of advice

was given to this young eager artist. At the time of the Apollo

11 mission a massive collection of Bonestell's work was shown

at the nearby Palo Alto medical clinic, where I examined many

of his originals and could see much that no reproductions could

show germane to the painting techniques involved.

Unfortunately, Willy Ley, who had done so much to

spread popular enthusiasm during the post-war era for what was

about to take place, died a couple weeks before Apollo 11's launch.

But he died knowing it was going to happen. Von Braun was capping

off his supremely successful multi-national career, and partly

due to his efforts Chesley lived to finally see and paint the

Moon as it really was, at the start of the 'Third Age Of Space'

which Ley had described in 'The Conquest Of Space'. This age,

one of human exploration of space, followed the age of telescopic

study, which was in turn preceded by that of what the raw human

senses could discern.

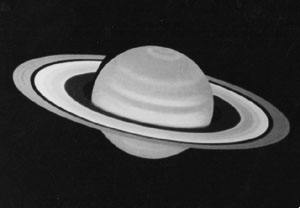

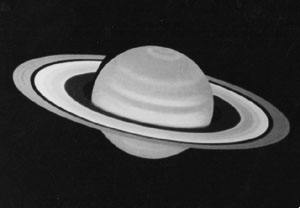

He told me the first space painting

he did was of Mars after seeing it in the then new 36 inch refractor

at Lick Observatory high atop the South Bay Area. Shortly afterwards

he did a painting of Saturn as seen through that telescope. Here

is a scan of a print of a version of that work he gave me while

making sure I had good references for the rings.

He told me the first space painting

he did was of Mars after seeing it in the then new 36 inch refractor

at Lick Observatory high atop the South Bay Area. Shortly afterwards

he did a painting of Saturn as seen through that telescope. Here

is a scan of a print of a version of that work he gave me while

making sure I had good references for the rings.

No artist saw as much of our perceptions change of

ones subject matter as did he. From imagining and painting a Mars

with canals, grassy plains, and no mountains he finally got to

paint the truth based on probes actually landed there. He lived

to know what asteroids looked like, how the Moon would be first

explored, and what a lot of moons unknown when he was born actually

looked like. Most of his pre space flight Moon paintings tended

to exaggerate the vertical relief of mountains, partly because

of their appearance in contrasty observatory photos, and partly

because of dramatic license inspired by the landscape elements

in Gustav Dore' engravings.

Among his advisors were giants in the space field, from Rocket

Men Willy Ley and Werner Von Braun, to Astronomers Robert S. Richardson

and Gerard Kuiper.

In the 'Seventies I began a long and rewarding series

of visits to Chesley Bonestell's house in Carmel, where his gracious

wife Hulda would entertain me and my girlfriends (and eventually

my wife) until Chesley would appear, take me up into his studio

up the stairs in the back, and look at whatever work I had brought.

He would look good and hard at it, tell me first the things he

liked about a particular work then about the aspects of the picture

he didn't like. He was ruthless and also enlightening to show

one's work to. He told you what he thought and you listened. I

came away from every visit determined to do better the next time.

He was highly educated, and enjoyed discussing ancient civilizations,

religion, politics, and of course art. He revered FDR, but despised

Truman. In one of the Colliers nuclear destruction paintings he

pointed out the White House blazing brightly, with reserved glee

saying he was glad to show Truman burning.

Among the many films he painted

background mattes for were 'Hunchback of Notre Dame' and 'The

Thief of Baghdad'. Once while visiting his studio in Carmel he

showed me a detailed photograph of one of the 'Thief of Baghdad'

city scenes, pointing out some ladies panties hung in a window

in the distance. He said it was a little joke of the kind he sometimes

would sneak through, this one appearing as a signal by a housewife

to let her lover know the 'coast was clear'!

Of the San Francisco Earthquake, Chesley recalled

being awakened after a short rest from partying by the tremendous

shaking and crashing, he started awake and exited through a ground

floor window, narrowly being missed by a piece of falling chimney

as he did so. He saw the streets suddenly filled with rats, running

from below the covered sidewalks and scurrying from one side of

the street to the other. This catastrophe impressed itself in

his artists mind and future paintings would treat the world to

possible disasters natural and man made.

One of his atomic war paintings, of the Kremlin being

destroyed, received an angry response from Soviet sources, which

called him a war monger!

Once I pointed out an old sepia tone photo of a group

of young men in suits, old co-workers with Chesley in New York.

I asked if anyone else in the picture was alive and he told me

no, he was the only one still living. During one such visit Bonestell

was working on the last of his major space art books, 'Beyond

Jupiter', which had several portrayals of the same Grand Tour

spacecraft featured in a Planetarium show I had just worked on.

The painting from this book I admired the most was the dim Mercury

landscape, lit from behind by Earth and Venus, with the ghostly

tapering Zodiacal light looming above the mountainous horizon.

It was Bonestell who first made me aware of the Zodiacal

light when I inquired about the bidirectional glow emerging from

the Sun in his paintings. At first I thought it was one of several

devices artists employ to suggest brightness, like lens flare

or a 'fogged lens' look. This is indeed a real feature, a thin

but wide lens shaped cloud of dust occupying the same plane as

the orbits of the Planets. Chesley said it is faint but quite

observable away from city lights.

When I first saw it years later delicately glowing

like a diffuse vague wedge it surprised me how large and noticeable

it can be under truly dark skies.

The importance of understanding

perspective was the first thing Chesley emphasized. It is like

understanding the rules of punctuation before trying to write.

The fundamental role of perspective drawing in this business was

repeatedly emphasized, and he even made a series of drawings for

me summarizing techniques for portraying objects in various perspectives.

It was often like drafting a three view drawing, with lines running

from the viewpoint to the object and the angles carefully noted

in the 'plane of the picture'.

He also showed me a good method of drawing ellipses.

Radial lines drawn from the centers of two circles (sized to the

major and minor axis of the desired ellipse) were connected with

right angles drawn from the places the lines intersected the circles.

Where the two sets of derived lines crossed (horizontal lines

from one, vertical from the other), an ellipse could be interpolated.

The more lines drawn the better the quality of the resulting curves.

Bonestell also told me of many of his painting techniques. In

his matte painting days he found a mixture of white, London Oil

Colours Windsor Blue and Burnt Umber made an excellent match with

a natural blue sky.

He painted using methods similar to those the Dutch

masters employed. Oil paints were applied with initial underpaintings

defining the overall tonal values refined by layer after layer

of thin glazes of oil paint suspended in translucent painting

medium. Black skies are a particular challenge with oils, the

'slope' of the irregularities of the final painted surface must

be confined to less than a few degrees if you want a region of

glossy dark blackness free as possible from highlights.

This is done with layers of paint sufficiently liquid

to lose their brush marks after application. Landscape details

are less important to keep smooth, but ideally all the 'modeling'

effects desired are portrayed rather than applied, to facilitate

photography. Among his many pieces deserving of comment are:

His painting of Palomar observatory, with golden

sunset clouds behind it. A more exquisite portrayal of the play

of light on solid forms would be hard to name.

The 'Antares' scene from 'beyond the Solar System'

(stolen, unfortunately) has a joyous play of multicolored light

in the clouds of an inhabited craggy world of a red giant.

The astronaut being buried on the rim of a Martian

crater is another of my favorites, reminding one of the unforgiving

nature of exotic frontiers.

Chesley made the universe seem

real to a generation who would one day help bring us images revealing

the true nature of many of the things he painted.

Don Davis

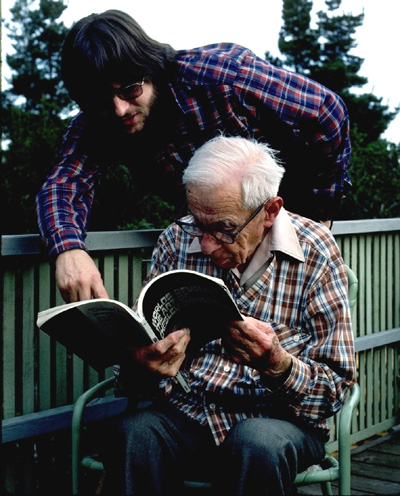

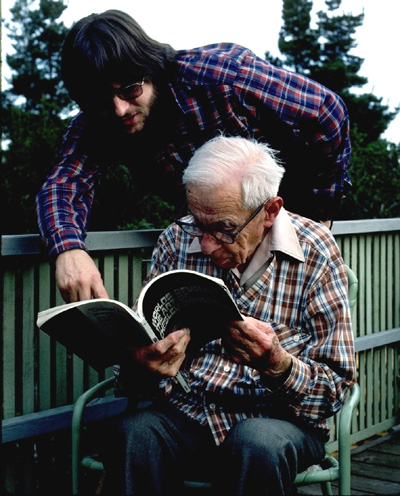

Chesley Bonestell and I looking at his

first art book at his Carmel house balcony.

Author Gregory Benford met me through referral

by Bonestell. My illustrating some of his stories first brought

my work science fiction magazine covers. This was the start of

innumerable appearances of my work in print over the coming decades.

Here is Greg Benford's essay 'View From Titan', which captures

a bit of the times and background of the beginnings of my publishing

career. For some reason I can't make this a hot link but copying

and pasting works fine:

http://web.archive.org/web/20080411043007/http://www.space.com/sciencefiction/benford_view_from_titan_000601.html

He told me the first space painting

he did was of Mars after seeing it in the then new 36 inch refractor

at Lick Observatory high atop the South Bay Area. Shortly afterwards

he did a painting of Saturn as seen through that telescope. Here

is a scan of a print of a version of that work he gave me while

making sure I had good references for the rings.

He told me the first space painting

he did was of Mars after seeing it in the then new 36 inch refractor

at Lick Observatory high atop the South Bay Area. Shortly afterwards

he did a painting of Saturn as seen through that telescope. Here

is a scan of a print of a version of that work he gave me while

making sure I had good references for the rings.