Text and most images © Don Davis

On

Painting and animation techniques then and now

1. Traditional painting

The creation of convincing astronomical

images, especially those with hardware or other geometry requires

knowledge and use of perspective and lighting principals as well

as a working knowledge of the subject matter. Next comes mastering

the nuances of your medium of choice for your given pictorial

goals.

One reason I gave up oil painting was the hassle of

achieving even dark photographable blacks in that medium. Bonestell

excelled in this, thanks to the use of oils mixed with a painting

medium he preferred ( 2/3 turpentine, 1/3 sun thickened linseed

oil, a dash of Cobalt Drier) which if added to paint in sufficient

amounts can cause the brushstrokes to melt away before drying.

If time is not that important a few layers of such 'black' applied

in nearly liquid state can end up as a wonderful enameled like

surface which nowhere deviates from the horizontal by more than

a few degrees. This can be lit properly to show off the rich blacks

against the sunlit surfaces below. Smooth board panels or smoothly

sanded gessoed panels are the preferred painting surface with

this method. I have only done one oil on canvas painting with

the sky done this way, as many sanded gesso coats were required

before the sky could be even started.

Acrylics freed me of the black sky hassles ( I still

consider oils the ultimate traditional media!) but only with the

computer can I be sure the skies will indeed look black in the

final printed page.

Many variations of what constitutes 'black' are done, from straight

use of 'Mars black' pigments to mixing up lots of deep thalo blue

and umber colors, or otherwise trying to tap in on blue's 'receding'

property. Geoffrey Chandler prided himself on never using black.

I am inclined to agree that black pigment should be no more than

a third of the volume of the color mixture I use for my skies

(if I ever paint a traditional media picture again!)

One place in an artist's work that almost allows you

to look inside an artist's mind is the way they portray randomness.

Pattern dominates efforts to mentally process textures

into paintable forms, but the forces which scatter rocks, stars,

and clouds about don't often behave predictably. The discovery

(or invention) of fractal geometry is a landmark in perceptions

of nature whose properties can be applied to such random things,

and has provided new textural possibilities for our work as it

has for our way of seeing things.Looking at my work of 20 years

ago, my painted attempts at rocky surfaces now look weird to me,

perhaps the computer makes me want to steer away from stylization,

an impossible thing and undesirable in many cases.

I am a worshiper of the look of the hyperreal, the

'take off my glasses and explore closeup' the micro textures nearby

while the distant vistas peek from behind the nearby stuff. A

simple Lunar landscape is among the most challenging textures

to paint, from the scattering of the rocks to the soil details

between the rocks. In space the distant scenery is distinguished

by concentration of textures into other 'meta textures' in the

distance, and by superimposition.

The photos from the Apollo missions are our best record

of being on another world, the later mission's surviving video

records have much to offer on behavior of dust in a vacuum, gross

lighting characteristics and variety of scenery on the Moon. As

such exploration continues to recede into the mists of history,

these sources will only grow in value.

Getting an impression across through ones work of

an unfamiliar place is obviously one of the things a skilled artist

can do with a vast variety of approaches, the skill is in tapping

into the visual cortex in such a way as to create a visual language

most of the audience can 'read'.

Much of the work of such

paintings has traditionally been the preliminary sketches in which

the composition and lighting are determined. Perspective drawing

and shadow plotting techniques have provided the means of trying

out the effect desired within the chosen composition. For the

quarter century from the start of my professional painting career

in late 1968 until the beginnings of my use of the computer with

regularity, labor intensive perspective drawings of things like

spacecraft and planetary ring perspective views accumulated in

folders with each new painting. Now most such preliminary work,

as with the primary act of painting, has largely moved to the

computer.

The creation of a desired

element in a picture justifies any approach taken to achieve it. In

other words, if it works, do it.

When Chesley Bonestell wanted to paint the rings

of Saturn as a line or an extremely thin ellipse, a technical

pen like a rapidograph would be used to outline the critical region

as delicately as needed, then he would paint (with oils highly

thinned with a painting medium) up to the line.

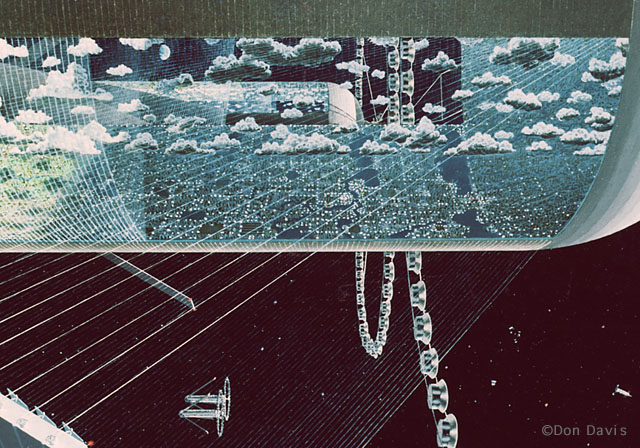

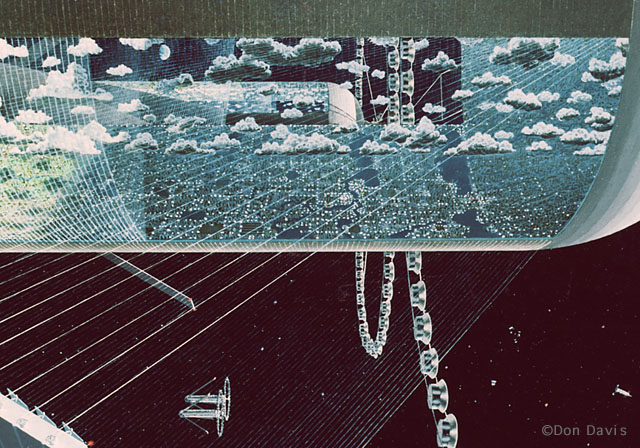

For a space colony oil miniature,

I opted to do it all in paint, including many cables nearly parallel

but showing noticeable perspective. After the background painting

was very dry, I hunched over the piece (about 12X16, oil on gessoed

Masonite) with a steel straight-edge suspended solidly on a knee

just above the painting. I had pecked tiny dots where each of

the cables began and ended, and anchoring my little finger on

the rulers edge I could glide my hand along just the right path

to let the fine brush paint a narrow line. This line had to be

thinner on one end to carry the desired impression of perspective.

Each cable had to be painted after shifting

the straight-edge and trying to insure just the right amount of

paint (of just the right consistency) was on the brush. During

the critical moments of painting the line the world disappears,

my being focused on becoming a precision machine. A mistake could

be wiped out with a 'Q-tip' dampened in turpentine, providing

the background is thoroughly dry.

Once layer 1 of the cables were dry, layer 2 could

then be safely painted! The results were....OK. Variations

of width were inevitable.

This is like a memory of a past life now, the turning

point for painting such things was my Galileo

cover for Sky and Telescope. The parachute lines were rendered

in 3D, and repainted in Photoshop. I wouldn't want to think of

doing them in traditional media, yet heroic effort used to be

part of such works. In the end I like the look of the computer

paintings for such hardware work.

A painter can create an image with an effective resolution

of, say, 2 pixels per millimeter (let's call that an average,

anyway) The standards for an acceptable print are a good deal

higher, roughly up to 10 pixels per millimeter.

When painting digitally, as I now do, it is important

to keep in mind the vast size such paintings must be to indure

good display prints and reproductions in print media. More new

work in shows will be digital prints, and there are advanced 'printers'

which even spray an image onto canvas and art board surfaces using

a digital file. I can see using such a device as an 'apprentice'

and finishing up the result by hand.

Over the years I became familiar with

the mathematical tools for calculating horizon distance, but I

never used them, and they lie buried among my copious notes. I

hated my math classes in public schools, and to this day I cannot

do anything but add, subtract, multiply and divide. Despite my

stunted math skills, I recognize the power and usefulness of mathematics

to our world and to such work as mine.

Now that I can 'look' at a virtual Earth with great

detail and create an instant 'perspective drawing' at a whim.

I can afford to try variations of views before committing myself. Only

the first preliminary drawings are still exclusively done by hand,

with my personal contribution to the painting concentrated on

the things computers do poorly or slowly such as various amorphous

details, and random things like rocks and other textures. Following

is an attempt to summarize some of my thoughts regarding the dawn

of the digital age in art.

2. Film and animation

When I became part of the Cosmos

team of artists in 1979, visual effects for films were still based

on traditional 'in camera' and model methods. Layering of images

beyond simple multiple exposures required the use of tricky and

very expensive optical printer work. At that time computer graphics

had just reached the stage of creating images of solid plastic

looking objects, but texture mapping was just being implemented

and ray traced cast shadows were still some time in the future.

All the shots of the surfaces of

other planets required the production of 'tabletop' sized models,

some built after design drawings I prepared. Although I was in

charge of the planetary surface landscape models, all of the artists

had some overlap of skills and it was common to join in on each

other's projects to help get something done on schedule.

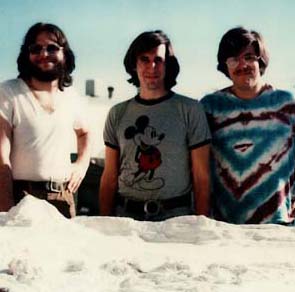

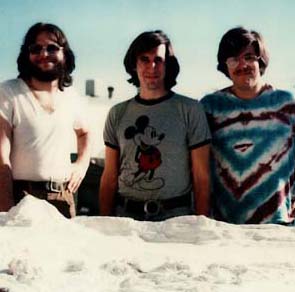

Left:

three Cosmos artists pose for a Polaroid as the first planetary

landscape

Left:

three Cosmos artists pose for a Polaroid as the first planetary

landscape model, that of Titan,

begins to take shape. Left to right: Don Davis, Jon Lomberg, Rick

Sternbach.

model, that of Titan,

begins to take shape. Left to right: Don Davis, Jon Lomberg, Rick

Sternbach.

Right: I am painting 'lava' flow details on

postulated 'ice volcanoes', the older surfaces were imagined as

a reddish brown color due to continuous deposits of dark 'rain'

of particles.

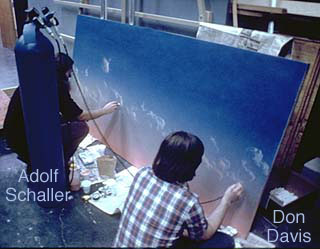

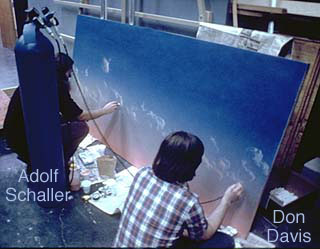

Left:

The background panel being painted, fortunately Adolf Schaller

and I handle clouds well enough we were able to create a work

of consistent quality. Most of the left side was painted by Adolf,

the right by me.

Left:

The background panel being painted, fortunately Adolf Schaller

and I handle clouds well enough we were able to create a work

of consistent quality. Most of the left side was painted by Adolf,

the right by me.

Below: The final painted backdrop behind

the finished model, ready for the cameras, rigged with tubing

for the bubbly vapor from the 'ice volcano'.

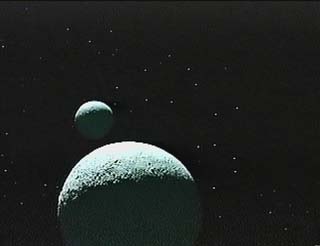

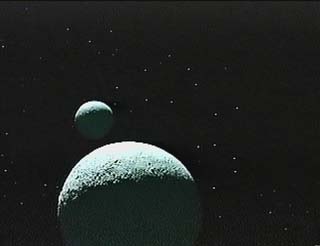

Many globes as well as planetary

surface models were made during the production. One shot was of

Pluto and it's then recently discovered moon. Charon. Two globes

were set up in front of a large sky backdrop made of perforated

opaque black sheets attached to a large sheet of frosted plastic,

strongly backlit with banks of lights. The shot depended, of course,

on the smoothness of the camera move as it was wheeled and moved

on it's crane.

Below left: the models, right: How the shot

appeared in the series 'Cosmos'.

3. The computer emerges.

My first

peek at a good computer paint system was in 1981, when I was asked

to paint a series of texture maps of Saturn, the outer planets

and some of their moons for the use by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

in upcoming Voyager encounter animations.

My first

peek at a good computer paint system was in 1981, when I was asked

to paint a series of texture maps of Saturn, the outer planets

and some of their moons for the use by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

in upcoming Voyager encounter animations.

At that time Jim Blinn, the originator

of many of the texture mapping methods now widely used, was working

at JPL and had written much of a then sophisticated painting program

which used an electronic stylus (with a cord attached) to apply

painting, or rather scratching motions on a flat 'tablet' which

caused blobs of a chosen color to instantaneously appear on a

monitor facing me, a miracle to behold then. Both Jim and Pat

Cole, another CGI pioneer, coached me in using the equipment.

Rick Sternbach had used the same system to create

texture maps for the earlier Jupiter encounter.

Unfortunately such systems were one of a kind major

setups then, a few years later the Quantel Paintbox was the best

electronic paint tool. Used for retouching of video elements,

time on such a system was fantastically expensive. A comet animation

sequence for the 1986 reissue of Cosmos was one of the few occasions

I actually got to paint for extended times on one. I had painted

with acrylics on acetate cels several comet landscapes which were

then shot on video and captured as high quality frames in the

Paintbox. I then painted with the electronic stylus many layers

of gas jets expanding and fading on frame after frame, which were

later cross dissolved in a video editing suite to create an animation

of dynamic erupting jets.

The first home computer I saw which allowed one to paint pictures

with a mouse was an Amiga in 1984, and I was not encouraged by

what I saw at that time.

Later glimpses of what Joel Hagen was able to create on an Amiga

nearly lured me to that platform, but fate intervened.

My 3 years career at Hansen Planetarium

in Salt Lake city started in 1987. During the process of my learning

the various aspects of show production I began my first continuous

relationship with computers. The Digistar computer graphic projection

system allows users to create detailed 3 dimensional models made

of lines and dots using a 'puck' (fancy mouse with cross hairs)

to trace outlines and contours while adjusting the 'working plane'

with a dial with the other hand to define where in the third dimension

the next line or dot will be placed. The show production dept.

purchased a number of Macintosh computers, and I was encouraged

to learn to operate them. After my first rocky encounter with

the UNIX operating system used by the VAX computer which powered

the Digistar, I found the Mac's intuitive approach a joy to use.

The first machine I began to play with was a Mac II with 8 bit

color, with I believe 8 megabytes of RAM, and an early paint program

called Pixelpaint. I learned to work around it's limitations and

create some images worth using. One Pixelpaint drawing tool in

particular, meant to simulate charcoal rubbing, was capable of

surprisingly subtle textures. During a visit by David Egge, it

was a delight to see how he became entranced with this same tool.

He sat until the early morning hours one weekend, building

up in rubbed textures a Mars landscape. One observation he made

then was that trying to paint with a Mouse was "like trying

to draw with a bar of soap", which I heartily agree with.

Later the Planetarium bought a crude scanner and an early

tablet, which allowed me to establish the rudiments of computer

assists for certain aspects of my art.

A series

of planet images were needed for a painting for JPL celebrating

the Voyager encounters, and for this painting I first used the

computer to generate a series of perspective views of the ringed

planets using a rudimentary modeling program called Mac3D, these

were photocopied to the desired size then taped together. I then

laid a sheet of tracing paper over this comp, and while producing

my 'master drawing' I would by hand smooth out the curves made

of many straight line segments making up a ring model, for example.

A series

of planet images were needed for a painting for JPL celebrating

the Voyager encounters, and for this painting I first used the

computer to generate a series of perspective views of the ringed

planets using a rudimentary modeling program called Mac3D, these

were photocopied to the desired size then taped together. I then

laid a sheet of tracing paper over this comp, and while producing

my 'master drawing' I would by hand smooth out the curves made

of many straight line segments making up a ring model, for example.

I could then cut out the separate friskits of the

planets and rings from copies of that drawing and went at it with

the air and paintbrushes. This acrylic on illustration board is

the result.

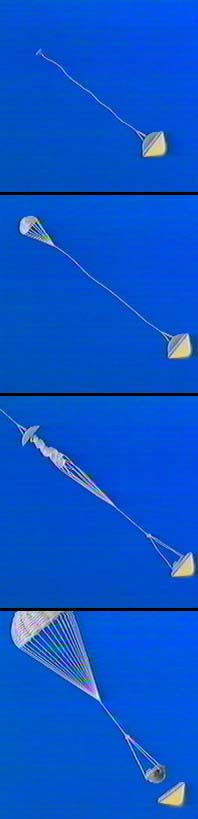

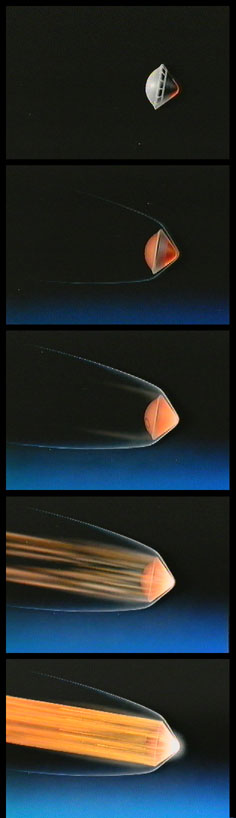

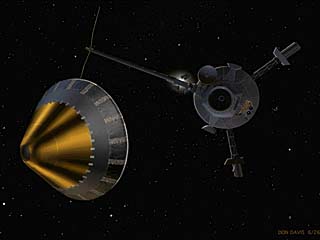

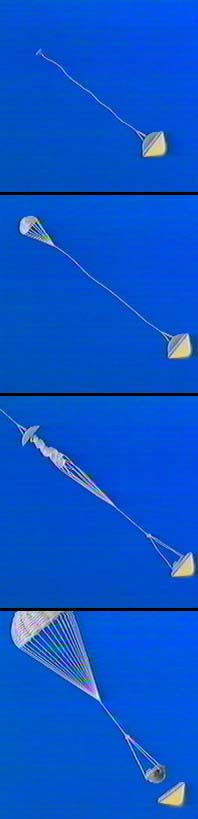

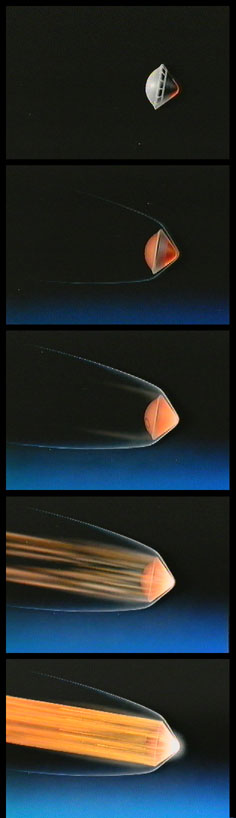

At

the time I was also working on an animation of the Galileo probe

entering the atmosphere of Jupiter, and simple models of the spacecraft

were made in the computer to allow accurate views to be rendered

and then traced on acetate cells from various angles. For

the probe entry sequence (left), I had to paint the fiery ablation

from the heat shield on hundreds of acetete cels. The sequence

of the probe deploying the parachute (right) also involved many

drawings, the parachute cords were all drawn on acetete with a

'rapidograph' pen using white ink. All sequences tried to follow

accurately the appearence and timing of the events in the entry

sequence.

At

the time I was also working on an animation of the Galileo probe

entering the atmosphere of Jupiter, and simple models of the spacecraft

were made in the computer to allow accurate views to be rendered

and then traced on acetate cells from various angles. For

the probe entry sequence (left), I had to paint the fiery ablation

from the heat shield on hundreds of acetete cels. The sequence

of the probe deploying the parachute (right) also involved many

drawings, the parachute cords were all drawn on acetete with a

'rapidograph' pen using white ink. All sequences tried to follow

accurately the appearence and timing of the events in the entry

sequence.

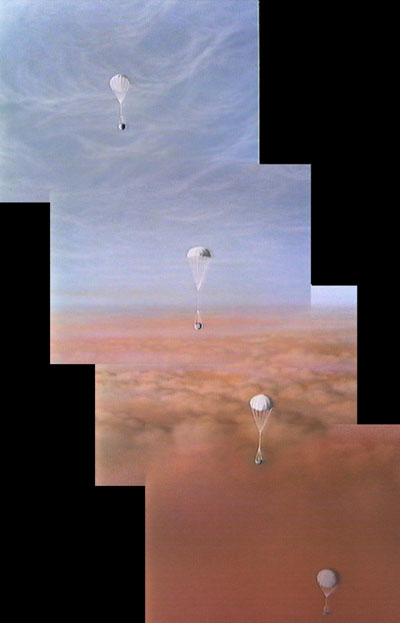

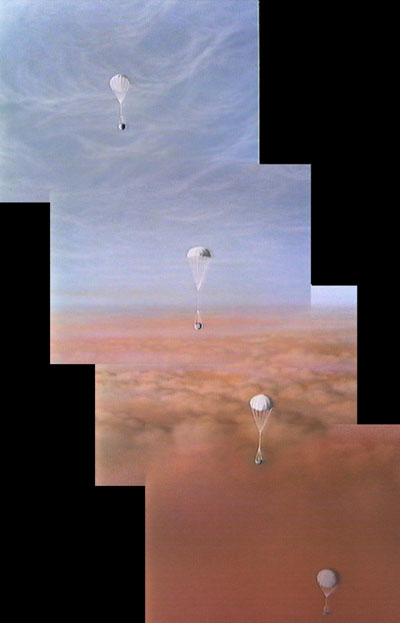

One sequence in the animated short (below)

used over a hundred 'Mac 3D' renders of a slowly shifting perspective

as the templates for the hand painted cels of the probe drifting

down near us from overhead. These frames were patched together

from a move which panned as it tilted, thus the black areas outside

the shot. This animation was the last time I used 35 mm movie

film as a primary medium. I painted, designed, and shot the film

myself, at times using 'bi-pack' mattes to combine foreground

action onto backgrounds.

During the Voyager

Neptune encounter I was in transition between Salt Lake city and

the Los Angeles area. I was starting to work for WQED science

effects, an effects house used for science related Public Broadcasting

shows such as 'Infinite Voyage', and 'Space Age'. At left is a

painting of the Voyager Neptune encounter, one of a series commissioned

by Charles Kolhase of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory of each of

the first Voyager encounters of the outer planets. All were based

on printouts of 'line drawing' representations of actual views

the spacecraft would see.

During the Voyager

Neptune encounter I was in transition between Salt Lake city and

the Los Angeles area. I was starting to work for WQED science

effects, an effects house used for science related Public Broadcasting

shows such as 'Infinite Voyage', and 'Space Age'. At left is a

painting of the Voyager Neptune encounter, one of a series commissioned

by Charles Kolhase of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory of each of

the first Voyager encounters of the outer planets. All were based

on printouts of 'line drawing' representations of actual views

the spacecraft would see.

During my career at WQED the transition

began in earnest in visual effects creation strategies from the

use of physical models and camera tricks to the growing digital

options. John Allison, a Cosmos veteran, headed the visual effects

facility in a converted warehouse in Glendale. We worked and played

hard there.

This is how we used to 'texture map'

a planet map onto a sphere before the days of computers! We prepared

an animated map of Jupiter's clouds, modified a 'wall' 35mm camera

to project the developed film onto a carefully aligned spheroid,

and filmed the result with our motion control mounted Mitchell

camera. In the case of Jupiter the limb darkening was even simulated

by a weak blue gel filter with a hole cut in it so when carefully

positioned in front of the light only the edges would be affected

from the camera point of view.

In other cases realistic painting or

modeling would be simply applied over a specially prepared globe,

such as this 12 inch earth globe I painted for the PBS 'Planet

Earth' series in the mid 1980's.

Many of these shots were simple

moves near the models against a backlit perforated black wall

such as had been employed during 'Cosmos'. Some shots, however,

required the use of 'mattes' to selectively expose parts of the

film at a time. These were prepared and literally sandwiched onto

the color film in the camera, using the precise, relatively cheap,

and very labor intensive 'bipack' method. A special 'double decker'

film magazine was required for this process, with one set of reels

holding the color film which was exposed twice in the long process,

the other set of reels holding the black and white film. Often

parts of the surroundings had to be painted out directly on the

film using a brush and opaqueing fluid, one frame at a time!

Many of these shots were simple

moves near the models against a backlit perforated black wall

such as had been employed during 'Cosmos'. Some shots, however,

required the use of 'mattes' to selectively expose parts of the

film at a time. These were prepared and literally sandwiched onto

the color film in the camera, using the precise, relatively cheap,

and very labor intensive 'bipack' method. A special 'double decker'

film magazine was required for this process, with one set of reels

holding the color film which was exposed twice in the long process,

the other set of reels holding the black and white film. Often

parts of the surroundings had to be painted out directly on the

film using a brush and opaqueing fluid, one frame at a time!

We soon realised that computer graphics

had not only evolved geatly in the last few years, they were becoming

available in affordable equipment and software. As soon as we

could we tried to 'automate' some of the tasks we were spending

days at a time on in some cases. We bought a Mac II FX, with the

then maximum RAM of any Mac at that time of 32 megabytes as well

as 24 bit color on a large monitor.

While at WQED

I learned Electric Image, then and still the best Mac rendering

and animation software. I also learned Adobe Photoshop, still

my favorite digital paint software. By then the painting and animation

capabilities available to users of such affordable home computers

had surpassed that of the original system I had painted the Voyager

texture maps with at the beginning of that decade. The

cheaply available electronic stylus now was not only cordless,

but pressure sensitive as well, allowing great subtlety in the

'brushwork'. I produced my first computer animation on the Macintosh

2 FX, of a proposed satellite called EOS.

While at WQED

I learned Electric Image, then and still the best Mac rendering

and animation software. I also learned Adobe Photoshop, still

my favorite digital paint software. By then the painting and animation

capabilities available to users of such affordable home computers

had surpassed that of the original system I had painted the Voyager

texture maps with at the beginning of that decade. The

cheaply available electronic stylus now was not only cordless,

but pressure sensitive as well, allowing great subtlety in the

'brushwork'. I produced my first computer animation on the Macintosh

2 FX, of a proposed satellite called EOS.

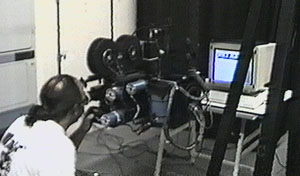

In order to get these early sequences

on film quickly we would actually set up the motion controlled

camera to look at the screen, and after trying out various contrast

adjustments and filter combinations we were able to obtain acceptable

video res 'film transfers' using this decidedly transitionary

method! Here John Allison makes the final adjustments before starting

the shot. During the cycle of exposing a frame in the camera

the computer in the camera system would send a pulse the Mac was

made to read as a 'mouse click', causing the next frame to appear

in the sequence. We would start a shot and leave the room until

the it was done.

4. The computer as a painting tool

Despite the traditional minority following

of Apple, the Mac is the artist's computer as shown by the migration

of large numbers of graphics people to that platform. The fact

is, however, that clever people can do great work on any of the

major platform choices. I now make virtually all my living with

my computer, my drawing board is used more for retouching damaged

old works and the preparation of that 'extra special' large painting

I keep promising myself I'll do.

Certain trends and changes in the methods of creating

images come to mind that digital media has imposed on the process.

The act of painting on the computer is at first totally alien

to the traditional tactile nature of creating art. The mark produced

is in a totally different place than where the 'pen' touches the

'drawing surface'. In a way, when I learned the use of the Passche

AB airbrush, I had to conquer a similar disturbance at seeing

a mark appear 'off axis' from the tool I was holding!

The Photoshop airbrush is quite good, and if used

at a very low percentage value a good varied buildup can be achieved.

Part of the effectiveness of computer airbrush

effects lies in the number of brightness levels available in the

picture. The current standard for home computer graphics is 24

bit, meaning 16,777,216 colors can be shown at any one time on

the screen.

I am told the human eye is capable of distinguishing

some 50 million colors or so, crowded in sensitivity along the

yellow to green transition of the spectrum. Thus 24 bit color

(and more so the larger color numbers used in high end digital

color work) approaches the ability of the eyes to perceive colors.

There is an important caveat to this, the limitations in the monitors

to accurately convey all the colors in the spectrum.

The color phosphors hit some parts of the spectrum

nicely and miss others badly, a particular example being the green

to blue portion. In order for the full color potential to be realized,

a high quality print or transparency must be prepared from the

picture file. Most monitors are tuned way too bright,

ideally areas of black in a picture should emit no light at all.

For visual relief the computer should be in a room where at least

one incandescent light falls across the walls, but not on the

screen. This supplies continuous light, that is a non flickering

illumination which will cover much of the visual field and reduce

the screen's fatiguing effects on many people due to it's own

subtle flickering.

With the advent of multi-layering in paint programs

new techniques of painting suggest themselves. a set of highlights

on a rocky hill can be painted atop another layer, then that layer

separately dimmed to see how a softer lighting would look.The

entire project can be saved at critical points to allow fearless

exploration that the traditional media of no return can restrict.

It seems that indeed the process of creating

an image is mutating beyond all bounds.

The use of the computer to do the perspective and part of the

lighting setup for certain hardware paintings has advantages in

that much of the perspective plotting 'donkey work' is now done

by the machine, allowing me to concentrate on painting the 'personal'

touches that distinguish the image from a purely CGI look.

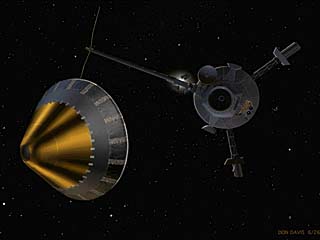

For a digital painting of

the Galileo probe separating from the orbiter commissioned by

NASA, I built in a 3D modeling program a complete Galileo orbiter

and probe, taking care to show the thermal coverings over the

instruments, the partly open antenna, etc. spending the better

part of a week on it. I then assembled the model within the Electric

Image software with appropriate color values assigned to the various

surfaces. No texture maps were applied, the idea was to compose

the picture and determine the lighting scheme.

Once I liked an angle, a simple wire frame render

was done of the spacecraft, black lines on white paper. This was

then faxed to NASA for approval. As things turned out, they didn't

like that or the second compositions, but because I could quickly

generate other angle views the third try faxed in that day did

the job.

Already the work of building the 3D model had been

justified.

Next a large (4096 pixels wide) image of the nicely lit model

was rendered in Electric Image, and the next 3 days were spent

painting on top of that render all the extra details specific

to that view using photos of the spacecraft as reference.

I thus let the computer do the work up to a point,

then took over where the human touch mattered the most, what is

normally the last ten percent of the work.

I think that even without significant painted embellishment, most

hardware art could now be done by machine, saving the inspired

painted images of that genre to people like Paul Hudson who continue

to display the inherent superiority of talented artists over imagery

created by people working in the realm of technology more than

technique.

Despite my absolute embracing of digital painting,

there are still pangs of regret in the demise of physical painted

surfaces as my primary technique, and I hope that traditional

media won't soon be forgotten. So much of a fine painting is not

reproducible on a phosphor monitor or even a high quality print.

The inner light of the fiery glazed painted surface

transcends the cold digital palette. A projected slide of a fine

painting shot in polarized light will surpass in richness and

subtlety all but the most expensive digital efforts to show the

same painting.

Ideally the computer is to be regarded as only another

tool to convey our inner visions to the world.

It is still necessary to learn perspective drawing

and how to draw by hand the things we see. Perception is sharpened

as we grapple with understanding and processing on a visual level,

then define our own understandable visual language to communicate

ideas with markings on a surface.

And yet the writing is on the wall. Ours is the last

generation to regard doing artwork in terms of purely physical

media.

Below:

an animated 3D model of an alien insect like animal which evolved

on a low gravity earthlike world, done for the Learning Channel

series, 'Cosmic Safari', produced by Invincible films in London.

Below:

an animated 3D model of an alien insect like animal which evolved

on a low gravity earthlike world, done for the Learning Channel

series, 'Cosmic Safari', produced by Invincible films in London.

Left:

three Cosmos artists pose for a Polaroid as the first planetary

landscape

Left:

three Cosmos artists pose for a Polaroid as the first planetary

landscape model, that of Titan,

begins to take shape. Left to right: Don Davis, Jon Lomberg, Rick

Sternbach.

model, that of Titan,

begins to take shape. Left to right: Don Davis, Jon Lomberg, Rick

Sternbach. Left:

The background panel being painted, fortunately Adolf Schaller

and I handle clouds well enough we were able to create a work

of consistent quality. Most of the left side was painted by Adolf,

the right by me.

Left:

The background panel being painted, fortunately Adolf Schaller

and I handle clouds well enough we were able to create a work

of consistent quality. Most of the left side was painted by Adolf,

the right by me.

My first

peek at a good computer paint system was in 1981, when I was asked

to paint a series of texture maps of Saturn, the outer planets

and some of their moons for the use by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

in upcoming Voyager encounter animations.

My first

peek at a good computer paint system was in 1981, when I was asked

to paint a series of texture maps of Saturn, the outer planets

and some of their moons for the use by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

in upcoming Voyager encounter animations.  A series

of planet images were needed for a painting for JPL celebrating

the Voyager encounters, and for this painting I first used the

computer to generate a series of perspective views of the ringed

planets using a rudimentary modeling program called Mac3D, these

were photocopied to the desired size then taped together. I then

laid a sheet of tracing paper over this comp, and while producing

my 'master drawing' I would by hand smooth out the curves made

of many straight line segments making up a ring model, for example.

A series

of planet images were needed for a painting for JPL celebrating

the Voyager encounters, and for this painting I first used the

computer to generate a series of perspective views of the ringed

planets using a rudimentary modeling program called Mac3D, these

were photocopied to the desired size then taped together. I then

laid a sheet of tracing paper over this comp, and while producing

my 'master drawing' I would by hand smooth out the curves made

of many straight line segments making up a ring model, for example.

At

the time I was also working on an animation of the Galileo probe

entering the atmosphere of Jupiter, and simple models of the spacecraft

were made in the computer to allow accurate views to be rendered

and then traced on acetate cells from various angles. For

the probe entry sequence (left), I had to paint the fiery ablation

from the heat shield on hundreds of acetete cels. The sequence

of the probe deploying the parachute (right) also involved many

drawings, the parachute cords were all drawn on acetete with a

'rapidograph' pen using white ink. All sequences tried to follow

accurately the appearence and timing of the events in the entry

sequence.

At

the time I was also working on an animation of the Galileo probe

entering the atmosphere of Jupiter, and simple models of the spacecraft

were made in the computer to allow accurate views to be rendered

and then traced on acetate cells from various angles. For

the probe entry sequence (left), I had to paint the fiery ablation

from the heat shield on hundreds of acetete cels. The sequence

of the probe deploying the parachute (right) also involved many

drawings, the parachute cords were all drawn on acetete with a

'rapidograph' pen using white ink. All sequences tried to follow

accurately the appearence and timing of the events in the entry

sequence.

During the Voyager

Neptune encounter I was in transition between Salt Lake city and

the Los Angeles area. I was starting to work for WQED science

effects, an effects house used for science related Public Broadcasting

shows such as 'Infinite Voyage', and 'Space Age'. At left is a

painting of the Voyager Neptune encounter, one of a series commissioned

by Charles Kolhase of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory of each of

the first Voyager encounters of the outer planets. All were based

on printouts of 'line drawing' representations of actual views

the spacecraft would see.

During the Voyager

Neptune encounter I was in transition between Salt Lake city and

the Los Angeles area. I was starting to work for WQED science

effects, an effects house used for science related Public Broadcasting

shows such as 'Infinite Voyage', and 'Space Age'. At left is a

painting of the Voyager Neptune encounter, one of a series commissioned

by Charles Kolhase of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory of each of

the first Voyager encounters of the outer planets. All were based

on printouts of 'line drawing' representations of actual views

the spacecraft would see.

Many of these shots were simple

moves near the models against a backlit perforated black wall

such as had been employed during 'Cosmos'. Some shots, however,

required the use of 'mattes' to selectively expose parts of the

film at a time. These were prepared and literally sandwiched onto

the color film in the camera, using the precise, relatively cheap,

and very labor intensive 'bipack' method. A special 'double decker'

film magazine was required for this process, with one set of reels

holding the color film which was exposed twice in the long process,

the other set of reels holding the black and white film. Often

parts of the surroundings had to be painted out directly on the

film using a brush and opaqueing fluid, one frame at a time!

Many of these shots were simple

moves near the models against a backlit perforated black wall

such as had been employed during 'Cosmos'. Some shots, however,

required the use of 'mattes' to selectively expose parts of the

film at a time. These were prepared and literally sandwiched onto

the color film in the camera, using the precise, relatively cheap,

and very labor intensive 'bipack' method. A special 'double decker'

film magazine was required for this process, with one set of reels

holding the color film which was exposed twice in the long process,

the other set of reels holding the black and white film. Often

parts of the surroundings had to be painted out directly on the

film using a brush and opaqueing fluid, one frame at a time! While at WQED

I learned Electric Image, then and still the best Mac rendering

and animation software. I also learned Adobe Photoshop, still

my favorite digital paint software. By then the painting and animation

capabilities available to users of such affordable home computers

had surpassed that of the original system I had painted the Voyager

texture maps with at the beginning of that decade. The

cheaply available electronic stylus now was not only cordless,

but pressure sensitive as well, allowing great subtlety in the

'brushwork'. I produced my first computer animation on the Macintosh

2 FX, of a proposed satellite called EOS.

While at WQED

I learned Electric Image, then and still the best Mac rendering

and animation software. I also learned Adobe Photoshop, still

my favorite digital paint software. By then the painting and animation

capabilities available to users of such affordable home computers

had surpassed that of the original system I had painted the Voyager

texture maps with at the beginning of that decade. The

cheaply available electronic stylus now was not only cordless,

but pressure sensitive as well, allowing great subtlety in the

'brushwork'. I produced my first computer animation on the Macintosh

2 FX, of a proposed satellite called EOS.

Below:

an animated 3D model of an alien insect like animal which evolved

on a low gravity earthlike world, done for the Learning Channel

series, 'Cosmic Safari', produced by Invincible films in London.

Below:

an animated 3D model of an alien insect like animal which evolved

on a low gravity earthlike world, done for the Learning Channel

series, 'Cosmic Safari', produced by Invincible films in London.